Our Long-Term Unemployment Challenge (In Charts)

More on:

The reasons why employment has lagged in the recovery remains a central challenge for macro policymakers, influencing the fiscal debate as well as figuring prominently in Federal Reserve justification for its current unorthodox policies. My colleague Dinah Walker points out a growing body of evidence that the problem of long-term unemployment is at the heart of the puzzle.

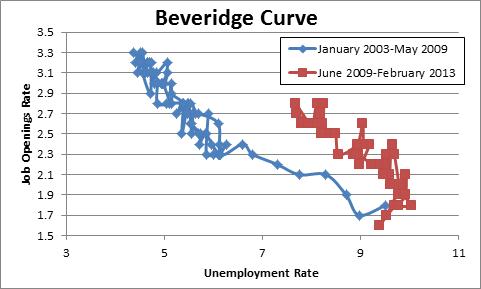

The Relationship Between Job Openings and Unemployment (The Beveridge Curve).

During most periods, there is a predictable relationship linking higher vacancies with lower unemployment. Since 2009, that relationship has shifted up–i.e., a given level of vacancies is associated with higher unemployment, suggesting a less efficient labor market.

It’s not unusual for there to be a shift of this sort at the start of the recovery, in part because firms may hold off on hiring until the recovery is more firmly entrenched. But the shift this time has been larger and more persisitent than is usually the case. Before 2009, a job openings rate (the number of openings divided by employment plus job openings) of 2.8% (February’s rate) would have been associated with an unemployment rate of about 5.5%, far below February’s unemployment rate of 7.7%.

Recent work by Rand Ghayad and Bill Dickens documents that, unlike past recessions, this time the breakdown in the relationship is concentrated in long term unemployment.

The authors did not find any evidence that the shift was concentrated in any particular sector of the economy, or across age or education. One theory of long term unemployment is that there is a mismatch of skills between what the long-term unemployed have and what firms want--recent work by Federal Reserve economists finds some evidence to this effect in the U.S. and a number of European countries--but if that was prevalent we would expect to see variation across these categories. Ghayad and Dickens go onto suggest though that a better explanation for the shift amongst those unemployed for longer than 27 weeks is that the long-term unemployed may be “searching less intensively–either because jobs are much harder to find or because of the availability of unprecedented amounts and durations of unemployment benefits”. For any of these stories, a puzzle is why the effects don’t show up in shorter-term spells of unemployment as well.

Recently, Rand Ghayad ran a follow-up experiment, sending 4800 fictitious applications for 600 job openings. The applications differed by length of unemployment, how often they switched jobs, and experience. What he found was long term unemployment dramatically lowers your chance of a callback. In fact, long term unemployed with relevant experience (the red line) were less likely to get called back than those that did not have relevant experience (the blue line), but who had a shorter unemployment.

Where does this leave us? Extended unemployment benefits appear to be contributing to the long-term unemployment challenge, and the rolling back of extended unemployment benefits should increase incentives to work. But this cannot be the entire story as there are good reasons to suspect that the loss of skills and connection to the job market provides a significant and lasting impediment to long-term unemployed reentering the workforce. Those unemployed for long periods of time tend to lose skills, look less attractive, and have a harder time finding jobs than those who have been unemployed for shorter periods of time. Expansionary monetary policy can boost overall employment and thus limit the rise in the pool of long-term unemployed, but has less ability to address those that have lost connection to the workforce. This puts the spotlight more on structural and fiscal policies, including measures aimed at helping those who are unemployed to find jobs and rebuild skills (earned income tax credit, job training).

More on:

Online Store

Online Store